Legacy Refactoring: Improving Testability of UI Code

Introduction

In September 2009 I taught a TDD & Refactoring class in Chicago with a great group of people. One of the questions that came up (and always comes up) is testing UI code.

UI could be graphical, textual, web-based, etc., but the techniques are the the same:

- Apply the SRP heavily.

- Use the humble dialog(object) pattern.

A more general principle is:

- Do not mix production code with enabling technologies. This is just a restatement of the SRP. But, for example, don’t put business logic in EJB classes; don’t put business logic in Servlet code.

These are good ideas; sometimes it helps to consider a concrete example.

In this class one of the students (Joseph Buschmann) brought me a simple, focused example he had created in C#. I started writing a Java version before I got permission to use his C# code, so since I had already re-created a simpler version in Java using Swing, that’s what this example uses. Note: This is the first Swing code I’ve written in 7+ years, so do not plan to be impressed with it.

What follows is an example of improving testability using some of the principles above along with some of Michael Feather’s Legacy Refactorings.

Background

Imagine you want to capture supplemental information about some product in your system. This additional information can either be text, html or a url. To capture it, you’ve created a UI control that captures the information and then validates it.

The Program

Here is the code for a program. Now this is certainly not complete and it certainly is not as complex as the code you have to deal with. Even so, it should be enough to demonstrate a few fundamentals.

Credit Where It’s Due

The idea for this example is from Joseph Buschmann. The Java code I’ve written borrows heavily from the Java tutorial. Specifically: How to Use Radio Buttons.

The Code

Here is such a program (greatly simplified when transitioned from C# to Java):

AdditionalDetailsPanel.java

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import java.awt.GridLayout;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.KeyEvent;

import java.net.URL;

import java.util.Enumeration;

import javax.swing.AbstractButton;

import javax.swing.ButtonGroup;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JOptionPane;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JRadioButton;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

public class AdditionalDetailsPanel extends JPanel implements ActionListener {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

private JRadioButton text;

private JRadioButton url;

private JRadioButton html;

private JTextArea textArea;

private JButton submit;

String errorMessage;

public AdditionalDetailsPanel() {

text = new JRadioButton("Text");

text.setMnemonic(KeyEvent.VK_T);

text.setSelected(true);

url = new JRadioButton("Url");

url.setMnemonic(KeyEvent.VK_U);

html = new JRadioButton("Html");

html.setMnemonic(KeyEvent.VK_H);

ButtonGroup buttons = new ButtonGroup();

buttons.add(text);

buttons.add(url);

buttons.add(html);

Enumeration<AbstractButton> elements = buttons.getElements();

while (elements.hasMoreElements())

elements.nextElement().addActionListener(this);

JPanel radioPanel = new JPanel(new GridLayout(0, 1));

radioPanel.add(text);

radioPanel.add(url);

radioPanel.add(html);

add(radioPanel);

textArea = new JTextArea(10, 60);

add(textArea);

submit = new JButton("Submit");

add(submit);

submit.addActionListener(this);

}

@Override

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

if ("Submit".equals(e.getActionCommand()))

if (handleSubmit()) {

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(this,

"Additional Information Stored");

System.exit(0);

} else {

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(this, errorMessage);

}

else

handleRadio();

}

private void handleRadio() {

textArea.setText("");

}

private boolean handleSubmit() {

if (text.isSelected())

return validateText();

if (url.isSelected())

return validateUrl();

if (html.isSelected())

return validateHtml();

errorMessage = "No type selected";

return false;

}

private boolean validateHtml() {

String body = textArea.getText();

if (body.length() < 10) {

errorMessage = "Html is not valid";

return false;

}

return true;

}

private boolean validateUrl() {

String body = textArea.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

errorMessage = e.getMessage();

return false;

}

return true;

}

private boolean validateText() {

String body = textArea.getText();

if (body.length() < 10) {

errorMessage = "Text description too short";

return false;

}

return true;

}

}For completeness, here is class with a main() function to bring this program to life (so now you can can manually test it!-):

Main.java

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

public class Main {

private static JFrame buildFrame(JPanel contents) {

JFrame frame = new JFrame("AdditionalDetailsEditor");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.setContentPane(contents);

frame.pack();

return frame;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

JFrame frame = buildFrame(new AdditionalDetailsPanel());

frame.setVisible(true);

}

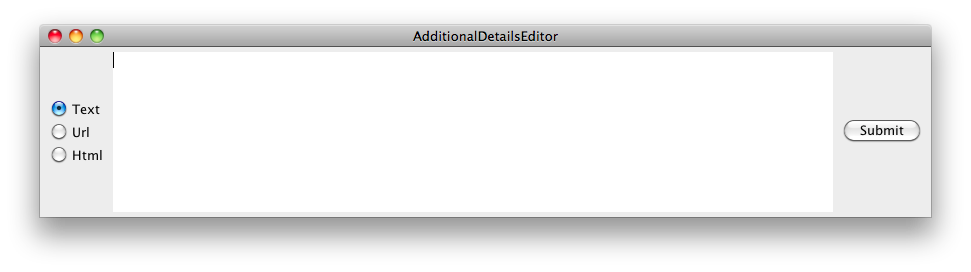

}If you run this example, you’ll see a rather ugly UI (the original one from Joseph Buschmann looks much better and uses different input widgets for the different kinds of additional information fields - the ugliness is all mine):

You might notice that there currently is no test code for this example. That is by design. To get to this point I had to run it and manually check it. This code is small enough and the example trivial enough that I got away with it (so far).

If this were “done” and not changing, the there’s no reason to do anything with this code. So let’s discuss a scenario where we need to make changes to justify spending time refactoring this code and introducing automated tests.

Some New Requirements

Imagine you’ve been given a new set of rules for validation such as:

- Validate that HTML is well-formed but only includes certain acceptable tags (e.g. no divs or spans)

- Validate that any css class includes some mandatory prefix

- Spell-check the text and perform some basic validation of text entires

- Spell-check the body of the HTML

- Verify that all URLs point to a set of known, authorized sites

- …

The point of these new requirements is to suggest that the code as is needs to change. As much as I’d like to have the time to go back and add in missing tests to existing legacy code (legacy code ==> code without tests), I won’t do that without a reason.

There are several reasons to add tests to code that currently does not have tests:

- The code needs to change to support a new feature

- The code needs to change to fix a defect

- The code has been producing a number of defects

Why take this approach? Imagine you have 1 million lines of untested code. If you randomly start testing code, chances are you will test something that won’t change. While I’d prefer to have tests over all of that code, the next best thing is cover what is changing.

How to Test

As written, this test requires a graphic context. If you were to create tests for this code as written, you would have a difficult time running those tests on a headless box. Even so, that’s not a very realistic problem, so let’s write a few simple tests for the URL validation path.

Here are two simple tests to verify basic Url validation that keep the code structure essentially unchanged:

** UrlValidationExampleTest.java**

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertTrue;

import org.junit.Before;

import org.junit.Test;

public class UrlValidationExampleTest {

private AdditionalDetailsPanel panel;

@Before

public void init() {

panel = new AdditionalDetailsPanel();

}

@Test

public void verifyAValidUrlPassesValidation() {

panel.setText("http://schuchert.wikispaces.com");

panel.getUrlRadioButton().setSelected(true);

assertTrue(panel.handleSubmit());

}

@Test

public void verifyInvalidUrlFailsValidation() {

panel.setText("bogus");

panel.getUrlRadioButton().setSelected(true);

assertTrue(panel.handleSubmit() == false);

}

}These two tests work. No graphic windows appear. They run fast enough. So do you see any problems with this approach?

- Created method setText(…)

- Created method getUrlRadioButton()

- Moved handleSumbitMethod() from private to package default

This may not sound bad. In fact the setText(…) method is probably a good addition. However, these tests are white-box tests. This means the tests are probably fragile. This class is small and simple, so there was not a lot of work to make these tests work. For a real system, this approach is certainly possible but even more fragile. Also, your classes are probably significantly more complex and would require many more “simple” changes to get this far.

Notice that to get the method under test we needed to expose a private method. If a private method is not easily testable through the public API of the class, it often means that the private method is a candidate to be a public method on another class. (This is again an example of violating the SRP.)

There’s another issue to consider. Assume, for the moment, that the new requirements are enough work that multiple people can work on them in parallel. Since all of the work is currently in the same class, the risk of merge conflicts is high. This is yet another manifestation of violating the SRP.

So while this approach works (and in my environment these tests pass), let’s consider a second approach.

Applying WELC Refactorings

In Working Effectively with Legacy Code,Michael Feathers describes several refactorings you can apply that have the following characteristics:

- They are (as all refactorings) behavior preserving

- They are (typically) smaller than many of the Fowler refactorings

- They introduce what Michal calls “seams” to make the code testable.

So many of us at Object Mentor use the phrase “welc refactoring” to mean:

A simple refactoring made without tests whose primary purpose is to make introducing tests possible. That is, given code without tests, these refactorings are done so you can write tests so that you can do the refactoring you originally wanted to do.

For this example, we’ll use one Michael calls Break Out Method Object (page 330):

- Convert a method by passing instance data into a class with a constructor and a single method

We are not going to do this exactly. In fact, we’re going to introduce a strategy to make the code more easily tested instead, but it is essentially the same thing. The difference is how the extracted class gets access to the data it needs to read/write. The two forms we’ll consider are different types of dependency injection.

As I continue working thorough this, I’m keeping all the code you’ve seen so far compiling and the tests passing.

Break Out Method Object

To apply this refactoring, we are going to make the following method work as a standalone class:

private boolean validateUrl() {

String body = textArea.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

errorMessage = e.getMessage();

return false;

}

return true;

}Before we do that, consider the following two lines:

String body = textArea.getText();

...

errorMessage = e.getMessage();The first line is problematic because it uses the textArea instance variable, which is a JTextArea. The second line is a problem because it sets a another instance variable. We could do this (don’t do this - though I did create a working version so you can give this a try if you’d like):

**New Class: UrlValidatorVersion1 **

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import java.net.URL;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

public class UrlValidatorVersion1 {

private final JTextArea textArea;

public String errorMessage;

public UrlValidatorVersion1(JTextArea textArea) {

this.textArea = textArea;

}

public boolean validateUrl() {

String body = textArea.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

errorMessage = e.getMessage();

return false;

}

return true;

}

}To make this work, we’d then update the validatUrl method to use this new class:

private boolean validateUrl() {

UrlValidatorVersion1 urlValidatorVersion1 = new UrlValidatorVersion1(textArea);

boolean result = urlValidatorVersion1.validateUrl();

if(!result)

errorMessage = urlValidatorVersion1.errorMessage;

return result;

}This “works” but it puts UI gunk in the UrlValidator class. Even so, this is an improvement. Here is a rewrite of the previous test class using this new extracted method object:

UrlValidatorVersion1Test.java

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertTrue;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

import org.junit.Test;

public class UrlValidatorVersion1Test {

@Test

public void verifyAValidUrlPassesValidation() {

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("http://schuchert.wikispaces.com");

UrlValidatorVersion1 validator = new UrlValidatorVersion1(textArea);

assertTrue(validator.validateUrl());

}

@Test

public void verifyInvalidUrlFailsValidation() {

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("bogus");

UrlValidatorVersion1 validator = new UrlValidatorVersion1(textArea);

assertTrue(validator.validateUrl() == false);

}

}There’s less setup. The code is directly hitting its target. This exposes the error message, giving us more we can easily test. Even so, we can do much better.

Keeping UI Code in One Place

Go back to the original validateUrl method:

private boolean validateUrl() {

String body = textArea.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

errorMessage = e.getMessage();

return false;

}

return true;

}First make a few internal improvements:

private boolean validateUrl() {

String body = getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

setErrorMessage(e.getMessage());

return false;

}

return true;

}Changes:

- The first line now uses getText() to retrieve text. This removes any knowledge of a JTextArea. (See, adding that method in the first test wasn’t so bad after all.)

- Use setErrorMessage(…) to set the error message.

Given this change, we can rewrite the method object. Rather that passing in what the method object needs in the constructor, this instead uses method injection:

UrlValidatorVersion2

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import java.net.URL;

public class UrlValidatorVersion2 {

public boolean validateUrl(AdditionalDetailsPanel panel) {

String body = panel.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

panel.setErrorMessage(e.getMessage());

return false;

}

return true;

}

}This is moving in the right direction. Now the update to the original validateUrl method is:

private boolean validateUrl() {

UrlValidatorVersion2 urlValidatorVersion2 = new UrlValidatorVersion2();

return urlValidatorVersion2.validateUrl(this);

}There are still problems:

- There’s a circular dependency between the two classes.

- This new version depends on something that uses UI gunk (which I think is a violation of the Dependency Inversion Principle).

- It makes testing worse because we have to pass in an AdditionalDetailsPanel

There’s a simple fix, however. We can extract an interface to capture the methods we need to improve the situation:

TextSource.java

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

public interface TextSource {

String getText();

void setErrorMessage(String message);

}By adding this interface to the AdditionalDetailsPanel and using it in the UrlValidatorVersion2, it makes the code more easily tested:

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import java.net.URL;

public class UrlValidatorVersion2 {

public boolean validateUrl(TextSource source) {

String body = source.getText();

try {

new URL(body).toURI();

} catch (Exception e) {

source.setErrorMessage(e.getMessage());

return false;

}

return true;

}

}Here’s the tests rewritten using a hand-rolled test double (a stub): UrlValidatorVersion2Test

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertTrue;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

import org.junit.Before;

import org.junit.Test;

public class UrlValidatorVersion2Test {

UrlValidatorVersion2 validator;

static class StubTextSource implements TextSource {

final String text;

StubTextSource(String text) {

this.text = text;

}

public String getText() {

return text;

}

public void setErrorMessage(String message) {

}

}

@Before

public void init() {

validator = new UrlValidatorVersion2();

}

@Test

public void verifyAValidUrlPassesValidation() {

StubTextSource stub = new StubTextSource("http://schuchert.wikispaces.com");

assertTrue(validator.validateUrl(stub));

}

@Test

public void verifyInvalidUrlFailsValidation() {

StubTextSource stub = new StubTextSource("bogus");

assertTrue(validator.validateUrl(stub) == false);

}

}This code is more focused, tests what you want to test directly and uses a standard technique to test code.

There’s an added bonus. The first tests took 0.9 seconds to run. That’s pretty fast, right? How long do these test take to run? 0.03 seconds. That’s 30x faster! It may not seem like much but imagine a system with 1000 tests (a small number, really). The difference is 900 seconds versus 30.

So this code is more easily tested and the tests run faster.

There’s one more problem I want to fix before leaving this. The name of the new method is validateUrl. It was called that because we had 3 validate methods in the same class (another classing SRV violation), so we needed to distinguish between them. Since we will end up with several little validators, let’s rename the method to validate.

If I apply this simple idea to all of the validation, I end up with:

HtmlValidator

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

public class HtmlValidator {

public boolean validate(TextSource source) {

String body = source.getText();

if (body.length() < 10) {

source.setErrorMessage("Html is not valid");

return false;

}

return true;

}

}TextValidator

package com.om.ui.refactoring.example;

public class TextValidator {

public boolean validate(TextSource source) {

String body = source.getText();

if (body.length() < 10) {

source.setErrorMessage("Text description too short");

return false;

}

return true;

}

}Here’s the original handleSubmit method:

private boolean handleSubmit() {

if (text.isSelected())

return validateText();

if (url.isSelected())

return validateUrl();

if (html.isSelected())

return validateHtml();

errorMessage = "No type selected";

return false;

}And after the rewrite, here’s an updated version (note I renamed UrlValidatorVersion2 to UrlValidator):

boolean handleSubmit() {

if (text.isSelected())

return new TextValidator().validate(this);

if (url.isSelected())

return new UrlValidator().validate(this);

if (html.isSelected())

return new HtmlValidator().validate(this);

errorMessage = "No type selected";

return false;

}For those of you worried about all the new’ing up of objects, here are a few comments:

- This is easily fixed by using fields.

- If you are running Java 1.6, these will be placed on the stack anyway (yes really).

Are We Done?

Yes! What?

Sure there’s more you could do. Not doing more might actually require more discipline. For example, we could:

- Extract an interface on each of the validators.

- Apply the Split Loop refactoring to separate the determination of which validator to use from the execution of the validator.

- Extract the determination of which validator to use into a factory method (or maybe even a factory class).

Making such a change would result in a handleSubmit method that looked like this (using just an extracted factory method - yes I did it to show what it looks like):

boolean handleSubmit() {

Validator validator = determineValidator();

return validator.validate(this);

}

private Validator determineValidator() {

if (text.isSelected())

return new TextValidator();

if (url.isSelected())

return new UrlValidator();

if (html.isSelected())

return new HtmlValidator();

throw new RuntimeException("Cannot determine correct validator");

}The rest of the code is also in need of some repair. However, the new requirements were aboutadditional validation. Stopping with just extracting the three classes is enough to support independent development of the validation and easy verification (writing unit tests), so there’s little need to go much further.

One more change I would recommend is making the nested StubTextSource class a public class since it will come in handy writing tests for all of the validators.

Conclusion

This code was initially testable but the tests ran slowly, had a great deal of internal knowledge (white-box) and where actually indirect (calling an actionPerformed method to test validation). Extracting individual validation classes was a great idea, but there’s more than one way to do that. The various ways don’t really involve a lot more time or effort but there are significant differences. Changing the code such that you can extract the class and have it** avoid** depending on enabling technology (swing widgets) is a better approach:

- It makes the extracted class smaller and more light weight.

- It allows that class to be used in more places.

- It makes the class easier to test.

While this example is trivial, the fundamental things you will want to do apply to your UI code. Actually, this approach is a general one that applies across technologies. It is worth practicing so making this kind of change is stored in muscle memory. In fact, you might consider this for a coding kata.

Final Questions

What about the GUI code?

Imagine if you had the business logic tested. What’s left? Flow, enabling/disabling fields & buttons, UI look and feel, etc. Some of this you can automate with any number of testing tools. However, before you do that, you might want to make the system configurable such that you can have a body-less head. That is, a UI with a test double back end.

Why? So that the UI tests you run verify flow, are reliable, run quickly, etc.

Do you never fully test the system

Youdo want to also write some tests that verify the fully connected system works. These tests are closer to smoke tests than full integration tests. They will have fewer checks because they are verifying that the system can be brought up in a fully-configured manner.

Comments